The cost of confusing ‘complex’ for ‘complicated’

1 July 2024

Errol Amerasekera

Let me start by stating the obvious – organisations and their leaders are confronted by a never-ending succession of problems and challenges. Their ability to effectively navigate these challenges is a critical determinant of the success of the organisation and its ability to deliver optimal performance.

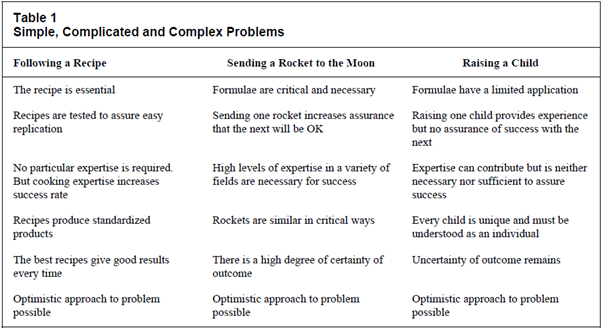

But all challenges are not the same! There are different kinds of challenges, and each requires a different strategic approach to its resolution. In recent times I have been mildly obsessed with a model that a colleague and friend – Joy Warmington, CEO of brap, shared with me. This model, developed by Glouberman & Zimmerman1, classifies the problems and challenges we face into three categories – simple, complicated, complex.

Simple challenges, for example, following a recipe, require no particular expertise to resolve. The solutions to these challenges are standardised, and thus replicable. Therefore, once we have constructed an effective solution to a particular challenge, such as following a recipe, that same solution can be used to resolve similar challenges. Following the same recipe, or utilising the same solution, should, in theory, deliver the same outcome every time.

Complicated challenges, such as sending a rocket to the moon, require greater levels of expertise, often from a variety of fields. Similar to simple challenges, processes, formulae, and procedures are essential in the resolution of complicated challenges, although they often require multiple and interdependent processes. However, because rockets are similar in critical ways, once there is a degree of mastery and success in sending one rocket to the moon, the process can be replicated with a relatively high degree of certainty in terms of the outcome. Examples of complicated challenges in an organisational context might be digital transformation or regulatory compliance.

Finally, for complex challenges, such as raising a child, standardised processes and procedures have limited applications. Every child is unique and must be understood as an individual, so the approach to raising each child must be uniquely tailored. So, while raising one child provides a certain degree of experience and expertise, there is little assurance that these same strategies will be successful with subsequent children. In fact, assuming that the strategies that were successful in raising a previous child, can be automatically extrapolated with different children, may well hinder successful outcomes.

Complex challenges require experimentation to unearth solutions that deliver optimal outcomes. We are therefore required to occupy greater periods of time in the unknown and the uncertain, as we, in effect, ‘reinvent the wheel’ every time we are confronted with a complex problem. In other words, essential in the process of addressing complex challenges is the ability to continuously innovate and transform our approach.

Constructing an effective solution to a complex problem is therefore primarily a cultural consideration because it requires psychological safety. Cultures that are psychologically safe allow innovation and creativity to be championed, even though there may not always be a guarantee of success. True innovation requires the courage to explore territories that are yet to be traversed. Driven by a desire for excellence, and a mantra of, ‘What if?’ innovative teams can experiment with new approaches to complex challenges knowing that, for every ground-breaking innovation, there may well be numerous failures. This can only happen in an environment where people feel safe to try new things, to take a risk, and have the freedom to fail, knowing that they will not be belittled or reprimanded.

A key feature of Glouberman & Zimmerman’s model is accurately classifying the problems and/or challenges we face into the appropriate category – simple, complicated, or complex. This is because in defining the type of challenge, we are better able to determine the most effective approach for how we go about constructing the solution; if the nature of the challenge is misclassified, the process we utilise in finding its solution may well be inherently flawed.

Many of the challenges that organisations, and their leaders face are complex; after all, leadership, in itself, is a complex undertaking. But also, building a high-performance culture is complex. Creating a diverse workforce is also complex. Unifying a team around a common goal or vision, whilst also supporting individual expression, is undoubtedly complex. Cultivating an inclusive culture that is built upon belonging and connection, is complex. None of these challenges have a simple or predictable solution, one that we can cut and paste from a previous experience without some degree of modification. While previous experience and expertise in dealing with these challenges is useful, they do not guarantee success, nor are they essential for the construction of new solutions. For many of these challenges, there are no established pathways, no predetermined protocols. Furthermore, while similar challenges may have been previously encountered, each complex challenge needs to be viewed with fresh eyes that are cognisant of the distinctive context and cultural positioning of the organisation in this particular moment in time.

Cultivating a more inclusive culture invariably requires us to address, at least to some extent, systems of oppression such as racism, sexism, homophobia, gender diversity, transphobia, anti-Semitism, and Islamophobia, just to name a few. These systems have deeply entrenched and effective ways of perpetuating themselves. Therefore, in how we approach the creation of a more inclusive culture, it is essential that we see this as a complex challenge, and then, deploy the appropriate strategic approach to best address this challenge.

However, at the limits of our capability – both personal and organisational – rather than a deliberate and concerted focus on addressing these gaps in capability, there can be a tendency to default to using patterns of thinking and working that are more familiar to us. When this occurs at the limits of our capability to innovate, to experiment, and to effectively ‘tolerate’ the tension of the uncertain, organisations and teams can confuse complex challenges for complicated ones.

As a result, solutions and strategies are constructed that may well be effective in the resolution of a complicated challenge but fall short in how they address a complex one. This can be costly. Firstly, because precious resources such as time, money, and personnel get diverted to a suboptimal strategy. And secondly, because complex problems almost invariably result in a cost to the organisation, this ‘cost’ could be a financial cost, a performance cost, a cultural cost, or perhaps even a well-being cost. So when the strategies we deploy to remedy the problem are suboptimal, and so fail to sustainably address the issue, these costs can be ongoing, and consequently be detrimental to the organisation.

Addressing complex challenges requires organisations and their leaders to develop two separate but related cultural capabilities. The first of these is to effectively classify challenges as complicated or complex (knowing that simple challenges are not usually the ones that create a significant risk or cost to the organisation, or keep leaders awake at night). Correctly classifying challenges means the strategies we utilise to resolve those challenges, will be most appropriate to the nature of the challenge itself. Secondly, given that confusing the complex for the complicated, often happens at an organisation’s cultural limits of innovation and creativity, fostering psychological safety so that these aspects of the culture can flourish, thereby extending those limits, now becomes a critical cultural capability.

Developing these capabilities, is in itself a complex challenge. Frequently, the problems we face instil within us a sense of urgency. And when captured by this urgency, we can create solutions to complex problems that are more reactive than innovative, more habitual than experimental. And while in this moment me providing a ‘simple’ solution to this challenge might be antithetical to the model itself, slowing down enough to ascertain the nature of the challenge, and then giving ourselves the space and time to experiment and innovate in how we construct the optimal solution, might well minimise the cost of confusing the complex with the complicated.

Please see our previous blog, Leading for Psychological Safety for more information on this subject.

1 Glouberman, Sholom & Zimmerman, Brenda. (2002). Complicated and Complex Systems: What Would Successful Reform of Medicare Look Like? Commission on the Future of Health Care in Canada: Discussion Paper No. 8. 8.